Shawanaga First Nation belongs to the larger Anishnabek Nation which stretches

across much of Ontario, east across the Prairies and around the northern shores of

all the Great Lakes. The Anishnabek Nation is comprised of Algonquin, Saulteaux,

Anishnabe (Ojibway), Odawa, Chippewa and several other groups.

Location/Size

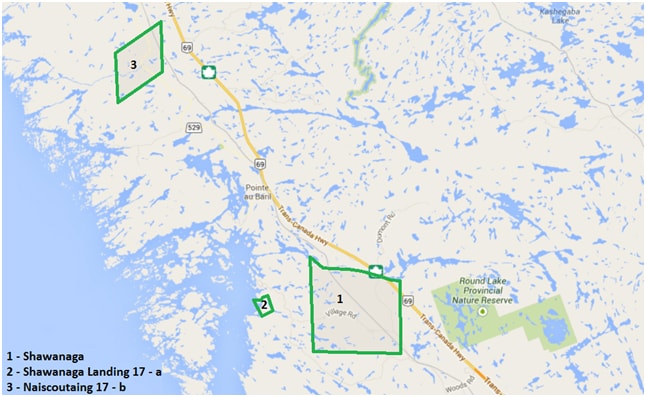

Shawanaga First Nation is located in Ontario at Latitude: 45.517 and Longitude: -80.284. The community is approximately 30 kilometres northwest of Parry Sound and approximately 150 kilometres southeast of Sudbury. The community has year-round road access from Highway 69 with a First Nation-owned gas bar and convenience store at the entrance to the community.

The traditional territory of Shawanaga is bordered by the Seguin River to the south, the Magnetawan River to the north and extending to Georgian Bay (including the 30,000 islands) and east to the Ottawa valley. There are three areas that make up Shawanaga First Nation: Shawanaga, Shawanaga Landing and Naiscoutaing.

History

Shawanaga First Nation belongs to the larger Anishnabek Nation which stretches across much of Ontario, east across the Prairies and around the northern shores of all the Great Lakes. The Anishnabek Nation is comprised of Algonquin, Saulteaux, Anishnabe (Ojibway), Odawa, Chippewa and several other groups.

In pre-contact times, Anishnabe in this region ranged from the Seguin River to the south, the Magnetawan River to the north, west to Georgian Bay (including the 30,000 islands) and east to the Ottawa valley.

Anishnabe traded fish and furs with the Wendat, who were farmers. Trade routes brought copper from the west and shells from the east. Leaders met together to maintain peace and alliances.

By 1760, after the Seven Year’s War, Britain had control over much of what they called British North America. But the indigenous nations sought affirmations and assurances of peace and fair trade, which led to the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The intent of the proclamation was to set out guidelines for European settlement of territories across Turtle Island (North America). It states that Aboriginal title exists and that all land would be considered Aboriginal land until ceded by treaty. Settlers could not claim land from indigenous occupants unless it was bought by the Crown and sold to the settlers. Indigenous nations insist that this Proclamation is still valid since no law has overturned it, yet First Nations continue to have to fight for and prove Aboriginal title and rights, and insist on consultation and accommodation.

A significant meeting between the English Crown and the indigenous nations of the western Great Lakes in Niagara in 1764 created what came to be called The Covenant Chain. The symbolism of the chain (with the three links of respect, trust and friendship) is that the Crown would hold one end and the indigenous people would hold the other end. The English Crown, represented by Sir William Johnson, presented a massive wampum belt, which symbolized and solidified the agreement and relationship. The Anishnabek became the keepers of the wampum belt, read and renewed each year on Manitoulin Island.

In the 1840s around Lake Huron, the Government sold ‘mining locations’ to individuals with ties to the Government. They began burning forest and blasting rock. In 1848, a delegation of Chiefs went to Montreal to petition the Governor General and complain about this situation. A Royal Commission showed that the land did indeed belong to the indigenous inhabitants and a treaty would be required to sell any more land to settlers.

William Robinson was named Treaty Commissioner in 1850 and he travelled along Lake Huron to negotiate what would be called the Robinson Huron Treaty. This treaty was intended to be an economic arrangement, with the following promises made by the Crown:

- Reserve lands to be held by the Ojibway people, unsurrendered, to use ‘for their own use and benefit’

- Cash payment at time of treaty

- Ojibway people would retain the right to hunt and fish on all Crown land, all unoccupied private land and in the water

- Perpetual annuity linked to the profits the Province made from the land

Shawanaga’s Chief, Muckata Mishoquet signed the treaty, though not when other First Nations in the area signed. It was signed two weeks later, at Penetanguishene, with neighbouring First Nation, Wasauksing.

There were many flaws in the Treaty, which is why Shawanaga First Nation continues to fight for respect, recognition and redress. These flaws include:

- The treaty commissioner’s secretary mistakenly understood the Ojibway word tibadagun to mean miles, when the Chiefs defined it as leagues, which is three times as big as miles. So there are major differences in what the Chiefs expected, what was described in the document and what was actually surveyed.

- Annuities did not increase after the 1880s and what was supposed to be meaningful support has become a symbolic pittance.

- Chiefs understood that fishing included fisheries; but fishing licenses were given to non-Ojibway commercial fishermen who overfished the lake and collapsed the fish stocks. Chief Solomon James of Shawanaga sent a letter to the provincial government in 1862 demanding an exclusive right of fishery from Shawanaga to Parry Sound, but his request was ignored.

- Provincial laws after 1890 restricted Ojibway hunting, despite treaty promises. Until the 1980’s, federal and provincial laws superseded treaty rights.

In 1905, a rail line was built through the community and a 100 year lease was signed between Shawanaga and CP Rail. The rail right of way takes up approximately 100 acres of Shawanaga First Nation reserve lands but no new lease has been signed since 2005.

In the early 1950s, Highway 69 was built on the northeastern edge of Shawanaga First Nation.